Sunaura Taylor: Lessons from a Wounded Desert

Today, our search lands us in conversation with Sunaura Taylor, a professor, artist, writer, and activist whose scholarship explores the entanglement of disability and ecological thought.

Her work at the intersection of disability studies, environmental justice, multi-species studies, and art practice invites us to see beyond traditional environmental narratives to appreciate the vital contributions of all forms of life, advocating for a more inclusive understanding of our planet’s health and our species' future.

Her latest book, Disabled Ecologies: Lessons from a Wounded Desert, is a powerful analysis and call to action that reveals disability as one of the defining features of environmental devastation and resistance.

Through her art and scholarship, Sunaura reveals the overlooked parallels between disabled bodies and the Earth's landscapes—both bearing marks of history and resilience.

In this time of ecological uncertainty and social change, her insights compel us to question how we perceive health, harm, and harmony in the natural world. To challenge us to think differently about ecology and disability, to embrace a broader, more inclusive vision of environmentalism, and the rights of nature, and ultimately, what it means to be human.

Today, we accept Sunaura’s invitation to experience the environment and our place within it as deeply entangled—where the conditions of Earth reflect and influence the conditions of all living beings. And to propose a solidarity that spans species and systems, leading to a deeper understanding of resilience and regeneration, and teaching us new ways to live and heal together.

Guest

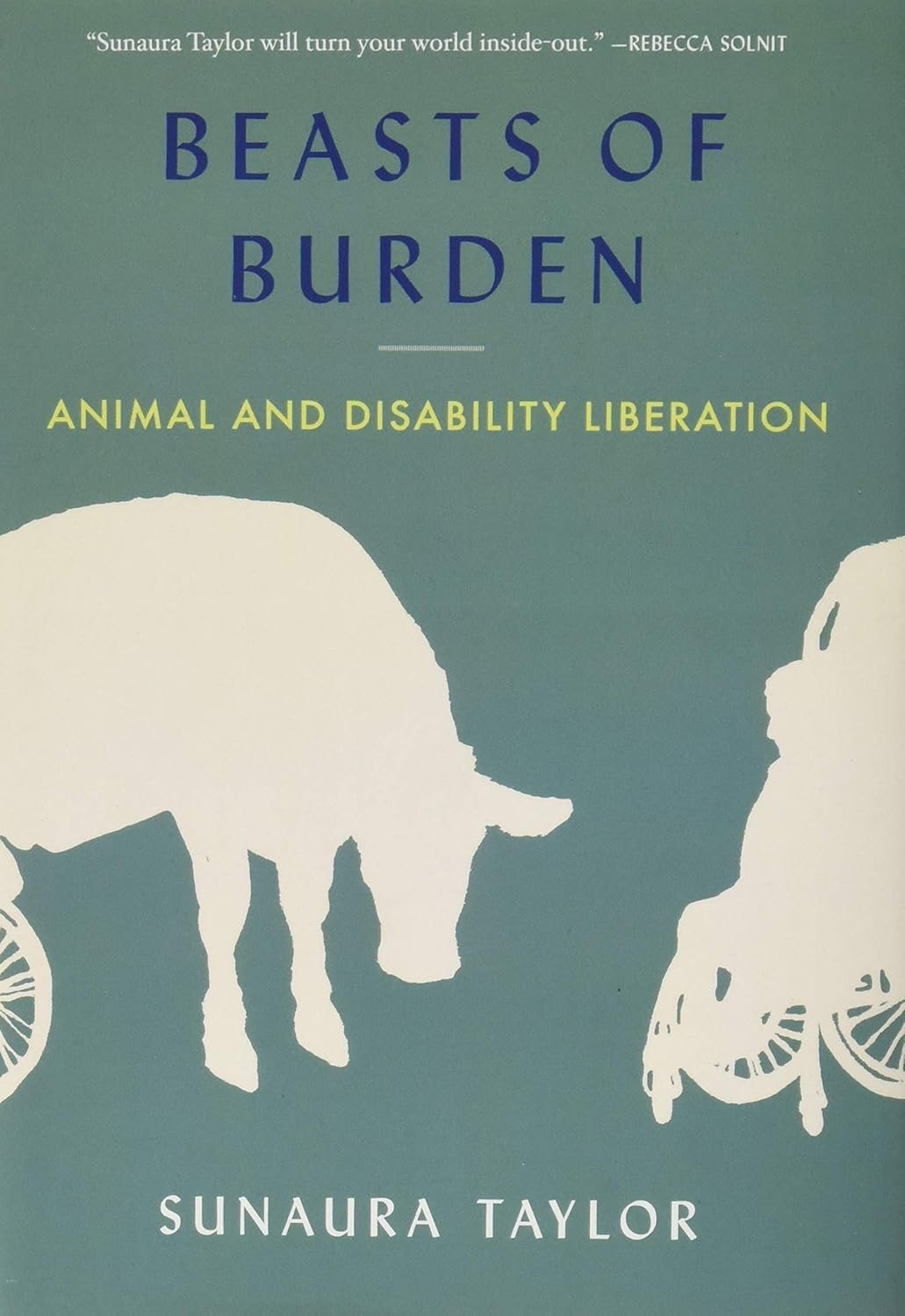

Sunaura Taylor is Sunaura Taylor is a professor, artist, and writer. She is the author of “Beasts of Burden: Animal and Disability Liberation”, which received the 2018 American Book Award, and her latest book Disabled Ecologies, Lessons from a Wounded Desert.

Taylor has written for a range of popular media outlets and her artworks have been exhibited widely both nationally and internationally. She works at the intersection of disability studies, environmental justice, multi-species studies, and art practice. She is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management at the University of California, Berkeley.

Sunaura lives in the Bay Area with her daughter Leonora, husband David, and their two cats, Rosie and Pirate.

You can find out more about Sunaura and her work by visiting:

www.sunaurataylor.net

From The Library

Extended studies from The Infinite Search library. Dive deeper with some of our favorite titles related to the episode.

Books

Transcript

[00:00:00] Sunaura: Thank you so much for having me. I'm really excited to be in conversation with you. And also thank you for that beautiful introduction. It's really meaningful to me to also hear the way that people sort of articulate some of these ideas. So that was really wonderful. Thank you.

[00:00:16] John: Absolutely. I really enjoyed the research that I got to do this episode and to, to read this book and learn more about Superfund sites and all the impact that you're having with, with the multitude of intersections that you have with your work.

[00:00:30] Before we get started, I would, I would like to make some

[00:00:32] space for an access check and a visual description of my space in light of learning more about disability best practices. Um, I know that our episode is only going to be audio only, but You know, learning more about your work. It was something that I learned from researching and, you know, being able to find a better way of creating a more accessible experience for all of our listeners.

[00:00:51] So I wanted to thank you for that. And so, um, I'm a multiracial white man with very long, dark Brown hair, tied up in a bun. I'm wearing glasses and a thrifted thrifted vintage green colored shirt with a yellow and Brown rectangular pattern. I'm in a part of my home studio with plenty of natural light. I have large, colorful pink and yellow paintings.

[00:01:10] Over a fireplace that is filled with some books, ironically, and next to that is a hutch with some green plants, a record player, speakers, and some of my favorite design objects.

[00:01:19] Sunaura: Um, so I am middle aged, uh, uh, white woman with short brown hair. I am also wearing a vintage, uh, uh, thrifted sweater, uh, we have, I was commenting when I first logged on that we have some, um, color echoes going on in our, in our spaces.

[00:01:39] I'm also in a pink light filled room. Um, I have some plants in here, but you can't see them that well. My dog is on the uh, couch next to me snoring. And Let's see what else I would say access wise, you know, access checks are so, uh, such an important part of disability culture, disability community, um, disability activism.

[00:02:03] They change, of course, depending on whether you're in a physical space with people or on zoom or, or in this situation, a podcast, but I really appreciate you starting with, with, with them. Cause they, they really help kind of change, change the, the, the narrative around what, who needs access and what access is.

[00:02:24] John: Yeah, absolutely. The, um, you know, starting off looking at your book, the, I was reading the dedication page and it had a number of comments on it, but. There was something that really struck me where you thanked your parents for gifting you with knowing what kind of stories to tell and knowing that I've read through this book and the kind of stories that I see that you're writing.

[00:02:45] I'm curious, in your, in your own words, what are those kinds of stories that you do want to tell?

[00:02:51] Sunaura: I love this question and I. You know, I credit my parents with a lot. I, my siblings and I were all unschooled, uh, which is a sort of a radical form of homeschooling. And my parents really raised us with this sense of, uh, curiosity, of investigation, of creativity, of really being sort of self directed learners.

[00:03:18] And all of that influence that they had on my life and my, my way of learning, I think is embedded in this whole project. But here I was particularly thinking about the, the sort of intimate relationship that I have and my family has with the story that I tell. So I tell the story of Um, or one of the things that the book does is tells a story of defense industry pollution on the South side of Tucson.

[00:03:49] This was the place that I was born and that pollution, I was raised with understanding that that pollution, um, likely caused my own disability that I was born with. So my family and I grew up, you know, or really like I was, I grew up with this story and my family, you know, my parents really. Articulated and this story to me from the youngest youngest age, right and what I value so much about how they framed it, right, is that it gave me very, very early on and understanding that disability was not sort of it.

[00:04:25] My own medical problem or individual problem, but that disability is a political issue. It's a social justice issue. It is an ecological issue and that disability wasn't something that I was experiencing alone, right? There was this whole community, um, also experiencing this injustice. And so that really opened up space later on in my life, which I won't get into right now in, you know, my twenties.

[00:04:51] When I discovered sort of more radical disability community to have to be so open to that because the whole sort of understanding of disability as political was already really shaped for me and, and, and, or really present for me as a young as a young person. So I think that that that sort of frame my, my parents.

[00:05:14] You know, offering a way of thinking about my own experience, uh, you know, growing up through this sort of broader lens of what the, what was happening in the world, what justice is, what it means to, you know, try to be a good person in the world. What it means to try to challenge, um, and, and fight back against sort of oppressive and, and systems and injustice.

[00:05:41] I mean, all those kinds of stories are the stories that I think my parents really planted early on, not only for me, but for all of, all of my siblings. Um, and so we have a, I think all of us have a sense of, you know, this question of like, what kind of people do we want to be in the world and what kind of work do we want to do?

[00:06:00] And I think then, as a writer and as an artist, kind of is articulated through, you know, what kinds of stories do I want to tell?

[00:06:07] John: Yeah, it makes me think about the language that we use and the difference between saying the word disabled and then the word ableism. How those are two ways of looking at something that seems like, to your point, it's such a political thing.

[00:06:22] And so I think that having that lens and those stories to tell is such a beautiful thing and something that's really needed to talk about more often.

[00:06:29] Sunaura: Yeah, I really, I appreciate you making that distinction because I think, you know, in a lot of, again, in disability studies and critical disability studies and disability activism, you know, there's, of course, you know, decades of sort of theorization and thinking about what it means to be disabled.

[00:06:46] Um, but also about what kinds of. Systems, um, are pressing right people who I who are identified as disabled, but even more than that, how this system of oppression, how able ISM actually is a force that. You know, reaches far beyond those people who we would think of as, you know, a label as disabled, right?

[00:07:11] And one of the things that I try to get across in both my books, in Disabled Ecologies and in my prior book, Beasts of Burden, is really the way in which ableism is a Is a sort of ideology, a system of oppression that does not just impact disabled people, but that impacts all, all people, as you say. And in fact, like non human animals, the way that we, the, the broader ecological world, it is an ideology, um, that sort of centers able bodiedness centers, ideas of what it means to be fit and healthy.

[00:07:45] privileges those ideas as the norm. And maybe, maybe I'll, I'm getting carried away with myself, but I'll, I'll stop there. But I think ableism is a really important concept to the book and to my thinking in general. So.

[00:07:59] John: I really loved the way that you framed your perspective in a multi species sort of way.

[00:08:04] You know, you describe it as a multi species story, emphasizing the interconnectedness of human communities with these various ecological elements. I'm curious. Can you, can you elaborate more on how you came up with that idea or how you're approaching this concept of a multi species way of challenging the traditional dualisms and taxonomic systems?

[00:08:25] Sunaura: Yeah, absolutely. So maybe if, if it's okay, maybe I'll dive into the, the history that I'm kind of telling a little bit to kind of get to these multi species entanglements. So from about the late 1940s through the 70s, Hughes Aircraft Company and various other weapons manufacturers, air, um, aircraft industries, uh, that were located in, on Tucson's south side, essentially, you know, just dumped their waste onto the desert floor, into desert washes, along the fences, abandoned wells, and into these huge unlined lagoons.

[00:09:02] This contamination, of course, eventually seeped down into the aquifer and then that water slowly made its way to the drinking water of the communities living above. By the time You know, when, when, when these industries were first moved in, it was quite a rural area. It was actually, um, quite a racially mixed area.

[00:09:27] Quite a, um, you know, these were good jobs for Tucson and stuff, but by the time the contamination came to light, it was largely a Mexican American community that was in the impacted area. That shift is due to a variety of sort of racist gentrification projects that had happened in other parts of Tucson that I tell the story of too, echoing the brilliant work of historian Lydia Otero.

[00:09:53] So a whole community of people drank. And it's kind of unknown exactly how many people, um, but, you know, tens of thousands of people came into contact with this water. And so, you know, I can get more into the details of what happened. There was this amazing environmental justice movement, one of the earliest movements in the country that formed in response to this contamination.

[00:10:16] But one of the, the, the things that I sort of was First struck by right was that like almost all cases of, uh, environmental harm. This was not something that only sort of that impacted only human beings, right? The groundwater, the aquifer itself was injured. The, there's all of these stories within the, the archive, the historical narrative of, you know, people realizing that there was something wrong in their community because their, their pets, or their farmed animals were becoming sick and, and, um, sometimes dying, or wildlife.

[00:10:59] Coming into contact with the pollution or trees in a contaminated area dying, right? So there's this sort of, you know, multi species web of injury there of who's impacted and what is impacted. And so for me, as someone who's long been interested in, uh, multi species thinking in thinking about what disability can help us understand, not only in terms of human experience, but in terms of how, you know, how disability shapes our relationship to the more than human world.

[00:11:37] I was immediately drawn to. Thinking about these injuries as connected, as inseparable. So instead of thinking about sort of environmental remediation over here as like the environment being impacted on one side, and then human beings being impacted over here, to really, you know, delve into this web of injury, what I call a disabled ecology.

[00:12:02] And so the multi species aspect of the project is so important because What I am, you know, essentially one of the main sort of goals of the book or, or, or things that I'm trying to address is just the way in which, you know, the health of nature and the health of human beings is inseparable, you know, and that, you know, There are some, in my opinion, really unhelpful things that happen when we think about them as, as, as separate.

[00:12:33] And so, following the sort of trails of disability, the multi species trails of disability, to me is, is a way of, of doing that. The last thing I'll say is that this is also something that I wanted to pull out because it's something that I see the organizers in Tucson and many other sort of environmental organizers, communities impacted by environmental, you know, injustice already doing, right?

[00:12:59] That, that there's not a sense that, that the separation between human health and environmental health isn't, isn't helpful, right? That there's, as, as people in Tucson often say, right, There's multiple things that need to be cared for the human community and the aquifer, right? Um, and so that kind of, well, I, they, community members and, and people I spoke to certainly weren't calling it a multi species justice.

[00:13:25] You know, that's sort of more academic language that multi species solidarity or thinking was so already there. And that, and it was something that I really wanted to, to highlight.

[00:13:37] John: It was fascinating reading that the indigenous communities were some of the first people to, to start to bring awareness to what was going on, regardless that they were ignored, but it was something I found really interesting was that.

[00:13:51] That's what they were talking about, to your point, you know, these, this interconnectedness, this entanglement is something that they've understood since forever. And it's something that our society is just now, I think, wrapping its head around.

[00:14:03] Sunaura: Yeah, you know, I mean, I think, you know, to, well, well, maybe I will first historically kind of lay out that, you know, this is, The area that I'm talking about are the traditional lands of the Tohono O'odham people.

[00:14:18] Hughes Aircraft actually moved in in the 40s about, you know, some, I can't remember exactly what the distance, but some extremely short distance. It's like, basically like, A mile away from the, what would it be? The north eastern corner of the San Javier reservation. And as you say, the, the representatives from the Tohono O'odham community were also some of the first to recognize that there was a pollution problem.

[00:14:49] There's actually a letter that I found in the archive making it clear. Clear that the pollution from Hughes was coming onto their land and killing their cattle and they there's this letter, that's this kind of incredibly prescient letter that would basically say, you know, this contamination, you know, if not stopped is going to be harmful to humans and and to to nature more broadly and that it's going to impact Pack the groundwater right this letter was came out decades before the contamination actually would be made public and of course nothing, nothing was done.

[00:15:29] In fact, this letter was written before he was actually even built. Doug, these enormous lagoons, which is then where a huge amount of bulk of the contamination came from. Right. So, you know, and and to your broader point, you know, a lot of people who I spoke to in Tucson gave me this longer history of what happened there that.

[00:15:52] There's this one sort of narrative, you know, promoted that by or kind of told by the polluters, but also by the EPA and other kind of government agencies that like this story starts in the early, you know, early 50s when these contaminate when when Hughes aircraft and these other industries started polluting, right?

[00:16:13] But community members tell me a much longer history, one of Colonialism and dispossession of, uh, native land and also the dispossession of, uh, Mexican American land and neighborhoods, right? Um, and so part of what I wanted to do was also really honor this, this longer history in this book. Because for Hughes to have been able to see this land as, Pollutable as available for the taking in the first place, depended on these sort of settler perspectives.

[00:16:48] What Natalie Avalos calls settler ecologies, this idea that nature is a commodity, right? Um, it's something property, not just something that one can is, is there for the taking, right? And I think that history. And that longer history was so important for me to tell the ongoing dynamics of that history.

[00:17:08] You know, I was writing this while Trump's border wall was being built on also on Tohono O'odham land, um, draining the aquifer, uh, and that portion of the land, um, as well. And so I have a brief section that's also kind of highlighting that. Yeah, and there's many other things that I could say, but I feel like I'm going on.

[00:17:29] So maybe I'll hand it back to you for and see where you want to take it.

[00:17:33] John: It's so interesting that you're talking about the EPA, because when we talk about this aquifer, you know, you mentioned that the EPA policies, they only deal with waterways. And that was something I didn't understand because I grew up near an aquifer and.

[00:17:46] To my understanding, it was the EPA takes care of the environment and that includes all the water, not just the stuff that is navigable. And it was just such an interesting that that's the case. And another thing I just kind of want to bring to people's attention is that, you know, we're talking about Hughes airport company.

[00:18:03] I work in branding and, um, so I'm very aware of why name changes happen in that sort of space. And the fact that they changed from Hughes airport to, uh, Raytheon. And then during your research changed from Raytheon to RTX and, you know, Raytheon and RTX are one of the largest global defense contractors on earth.

[00:18:24] I just, I had to bring that up because it was something that I didn't understand that they were Hughes to begin with. And so it was really interesting to see that, as you're talking about histories that are more than just one generation, that this is, an ongoing conversation around settler colonialism and that sort of perspective on environmental resources to maximize profit at the expense of all living life forms.

[00:18:48] Sunaura: Yeah, absolutely. And that it's a, and that it's also right. It's this sort of global extraction, right? That rate that That, that Raytheon now, uh, became RRTX actually right as the book was going into publication. So it's, so, it's Raytheon in the book, but that the sort of disablement of ecologies of environments, of human beings, of non-human animals, of aquifers, of waterways, right?

[00:19:14] This is, this is what these weapons manufacturers. Profit in this is what I mean, if we look at what's happening in Gaza, the mass disablement that is emerging from, um, weapons that are that some of which have been built and the same Tucson site. Um, so, you know, I was just speaking about how many of the folks that I spoke to.

[00:19:37] To in Tucson kind of have this long history, but they also have this deeply sort of a future oriented understanding to write that this is not something that this story is not just in the past that this that this is ongoing, right? That not only are the, the, the community still living with the impacts of illnesses and, and, and just the trauma of experiencing that, but then also, right?

[00:20:01] These industries are continuing perpet continuing to perpetuate arm. Uh, so. Your yeah, your your your thoughts about about the navigable waters and stuff. I want to return to. So, um, I think in the section you're referring to is when I'm actually talking about the Clean Water Act, specifically. So not the not the EPA more generally, more broadly, um, that.

[00:20:23] Uh, up until actually very, very recently, I, I just learned through research, this of course always happens when you put a book out, right, uh, eight years of research, but I just learned that this was actually just recently changed a little bit, but in the decades that the Clean Water Act has existed, basically that aquifers weren't really covered by this act, that the act really only covers the nation's, uh, navigable waters waters, those waters that, you know, one could have a vessel on. And so there's been a lot of pushback, especially in the past few years, as groundwater contamination has become such a profoundly serious problem. And also as the, the health of the nation's wetlands are, you know, so much more a part of the conversation that these different kinds of environments need to be considered.

[00:21:14] And so I'm not a, I'm not a policy expert, but my understanding is that There was just a change to the Clean Water Act in their definition of waters that does not remotely go far enough. It does not protect aquifers, but it says that if there's contamination that Like, let's say a company dumps their contaminants onto the ground and that seeps into the, you know, into the aquifer, and then a mile away, it reaches a water source that is used for drinking water or for, for human uses, that then that can be covered by the Clean Water Act, but there's some very bizarre, my understanding, again, as not a policy person, there's some very bizarre things around, well, not if it's like, you know miles and miles away, then somehow it doesn't, it's not under this juris jurisdiction or not if it's, there's all these limitations in loopholes essentially. So, but the broader point is that aquifer protection laws are really, you know, they need a lot of work to catch up to. Um, and obviously our nation's, the water in general, our nation's water needs to be protected more.

[00:22:24] But aquifer protection laws particularly are not strong enough and they will often sort of protect aquifers in terms of their Use for groundwater, but not as sort of broader ecological systems, not as vital parts of the not as vital parts of the environment. So maybe, maybe there will be some legislation about protecting the groundwater from contaminants and stuff.

[00:22:52] But in terms of depletion. These other kinds of dynamics that also would impact broader ecosystems. That is, you know, an area where there's profound lack of protection, which is why we're seeing such just terrible, um, levels of, of extraction and depletion of, you know, like world's aquifers right now. But again, I'm not a policy person.

[00:23:14] So, you know, this is all, um, uh, my, my understanding. Um, and then there was a third part of your question, but I just got so excited by the, by the aquifer that now I'm trying to remember what, what that other part of your question was.

[00:23:30] John: As we're thinking about this idea of the collective relationships between these systems, you know, one of the things you mentioned in the book was that our bodies are land and I'm, I'm curious to, what are you trying to say with that idea?

[00:23:44] Sunaura: And actually, this reminds me of something that I wanted to say to one of your previous questions, but then I, I got lost in my thoughts, but that is that, you know, this whole kind of concept that I'm getting to write that, uh, human health is inseparable from the broader health of our, Multispecies worlds, right?

[00:24:03] I really emphasize in the book and I really, of course, you know, want to make clear that, right, this is not a sort of a novel idea that I, you know, that I'm coming up with or anything, right? This is the, this is on some level, a perspective that so many indigenous communities, marginalized communities have, have understood for profoundly long time.

[00:24:31] The dynamic that I wanna make clear in the book, right, is that the separation, the idea that human beings are separate from nature and that our health is separate from the, the health of, of the wellbeing of the rest of the natural world, that humans are superior to na, to nature, to another non-human animals.

[00:24:48] These are, again, concepts that are profoundly rooted in settler colonialism and racial capitalism, a, a settler colonial perspective. Fundamentally needed to promote an idea of nature as property, as nature as commodity, and that is fundamentally at odds with so many other kinds of ways of understanding nature.

[00:25:16] And our place within nature, our place with the land, uh, human, human's relationship with the lands that then, you know, needed to be kind of crushed and stomped out, right? And so this section that you're pointing to, our bodies, our land, is really a section where I'm trying to sort of untangle some of these, some of these other kinds of, Histories and perspectives that the work that I'm trying to do here in terms of bringing human health into an ecological conversation that again, this is this is only necessary because of settler colonial perspectives.

[00:25:55] Um, Yeah, does that make, did, did that make any sense?

[00:25:59] John: Yeah, I think so. You know, we wouldn't have to have this conversation if it weren't for capitalism. You know, I, I see the relationships between what Hughes is doing and what they did in slavery. To me, those, these are the same things that we're minimizing an other and othering people and places that are part of our family.

[00:26:17] And part of our community and that when we don't respect and care for people, you know, I think about in psychological terms the idea of internal family systems multiplied on a, on a national level. And when we don't take care of all of our parts. It affects the whole, every time.

[00:26:32] Sunaura: Yeah, and I think, you know, for, for me, I think the through line for so many kinds of systems of oppression is commodification, right? When there's this desire to extract as much value from other beings, from other communities, from land as can possibly, uh, you know, it can happen, you know, just extract and extract and see other beings and our natural world as commodities, that that is so often a root of so much of the harms that we continue to see.

[00:27:06] John: You know, I want to get into the conversation around the aquifer that we're talking about and your artistic connection to it. And one of the things I read about was that your, your way of looking, you know, the way that you see things is the way is through is through painting. How did you incorporate that approach in your artistic process? into working with learning more about the aquifer.

[00:27:27] Sunaura: Yeah. So my background is really as a visual artist. I spent, you know, probably two decades of my, um, younger adult life as a painter, essentially. And, uh, So that practice is really important to me.

[00:27:45] I'm a visual thinker. I'm, I'm, I always feel like I, I, I think visually, I think one of the reasons why I like writing actually even more than, you know, uh, um, I'm more comfortable writing than I am also just kind of speaking off the top of my, my head. Cause that it on one level is also a visual practice.

[00:28:04] And that's just how my, my mind works, how I think. And so when I started writing, I didn't lose that. It became just a part of a, a different kind of method for me. Um, so both of my books actually have really started as visual, as visual projects, drawing and painting to me are also so powerful and useful because they can be, at least for me, they're places, right, where they're kind of unhindered by academic convention by like citational practice or by anything like that. Like it's really just like I'm thinking about these two seemingly totally random disparate things at the same time and suddenly they're emerging in the on the page. And that is a really creative and inventive space for me. And. Again, both of these books actually sort of began through that creative project process of being like, what is conceptually happening here on the, you know, with these drawings, and then really exploring them and taking them seriously and that leading to a research process.

[00:29:10] So that's one part of the drawing process. In Disabled Ecologies, I have a section of drawings that I call speculative aquifers that essentially are sketches of my changing, um, shifting understanding of, uh, what an aquifer is. I, like many people, had never really thought much about aquifers before researching this book.

[00:29:38] I sort of had a much more infrastructural vision of, of aquifers, you know. Again, you don't hear very much about aquifers as sort of, uh, broader parts of our ecosystems. You hear about them in, you know, their yearly yield or like, you know, the, the, again, the sort of commodification of groundwater.

[00:29:57] And so when I realized that, You know, it kind of hit me like a ton of bricks that it's like, Oh wait, the aquifer is sort of one of the central characters here. And actually I don't really understand how they work, you know? And so I wanted to learn as much as I could about aquifers. And part of that for me, Right, because aquifers aren't visible, they're underground, right?

[00:30:21] One of the hydrologists that I spoke to compared, compared the study of aquifers to the study of outer space, because it takes a lot of imagination to understand what's actually going on under there, right? Um, and so, for me as a visual person, I think starting to draw Um, My changing understanding of aquifers kind of became an important element.

[00:30:39] And so I include these drawings, these sketches, in the work. And I also kind of link them to a broader question throughout the book of what it means to be a disabled person, sort of, Uh, participating in the genre of nature writing that is often not a space that disabled people have historically been included in, right?

[00:31:02] Nature writing is filled with able bodied people conquering mountains and, you know, working out for months on end so that they can climb that next, you know, next steeper, this idea, right? Uh, to be intimate with nature is to be alone in nature or these, you know, so a lot of people have have sort of Engaged with the field of or traditional fields of nature writing for their sort of masculinist kind of tendencies and I think part of that is also Um, and their whiteness, right, but part of that is also their, their, their centering of able bodiedness and certain ideas of fitness.

[00:31:41] And so, throughout the book, I'm interested in what it means to be a disabled person participating in nature writing, and what a sort of a crip connection to nature is, and so the drawing practice is part of that as well.

[00:31:53] John: It was interesting seeing the imagery that you were producing as it progressed through your research, there was this sort of fidelity that came into view where things started to see a little bit more refined.

[00:32:04] But at the same time, there was almost this like abstraction where you were starting to entangle, I guess. And, you know, to use your own phrasing, your own bodiness with the aquifer itself. And I found that there was one specific image where you're incorporating hands into the visualization of this aquifer that. It was one of those things that helped me kind of make that connection between my own body, my own actions, my own thoughts, and the relationship of the nature that I've lived within and in, I just, I found that really arresting, actually.

[00:32:31] Sunaura: Yeah, thank you. So there's one image that was one of the later ones that I did.

[00:32:36] I was learning about a concept called losing reach, which is when an aquifer has become depleted and no longer can reach the, the water can no longer reach the above ground river, or, um, Riparian ecosystem, you know, there's basically a separation between that is forced between the above groundwater and, and the groundwater at this point, by the time I was reading about this, I had completely fallen in love with aquifers.

[00:33:02] Like now I'm just obsessed with aquifers. And, um, especially in the desert, you know, the desert is so dry and, you know, when it's not monsoon season and we, and so there's something so profoundly magical about realizing that there's this ancient, ancient water that's being, you know, held underground. And then something so tragic about the fact that it's just being sucked up for, you know, for mining, for cattle industries, for agriculture that doesn't work out there, for just the endless growth of cities in the desert and such.

[00:33:39] And that image really reminded me, I felt very connected to it because I don't use my own arms. And so this idea of things being out, like, sort of, of losing reach, of things not being reachable, um, and so I did, I draw my own arms sort of coming out of the, the riverbed, um, sort of reaching unsuccessfully for the river above.

[00:34:03] Yeah, so on one level, the images became more sort of, abstract, more entangled, as you say, more metaphorical. But to me, I think in that they also maybe become more representative of what is actually happening than my earlier imaginings that were again, much more sort of infrastructural and, and, and such, because I think if anything, about aquifers, they are fundamentally entangled with other aquifers, with above ground water, with water systems, with weather patterns. And I find that fundamentally really beautiful and fascinating.

[00:34:37] John: Yeah. Learning more about the reasons why you were creating that sort of, especially that one last image. It gives me this thought that it's also, um, I thought that or a feeling that maybe many of us are having around this out of reach goal that we're trying to fix things and we're trying to course correct and we're feeling out of reach of what is really needed to happen.

[00:35:00] It leads me into this next kind of question or conversation around the One Health discipline. It was something that I had no awareness. You know, I'd never heard of that term before, before researching your work. So I'm curious if you can just talk a little bit more around what that is and how it related to your research.

[00:35:17] Sunaura: Yeah. So there is a, I don't know what you would call it, a, uh, disciplinary approach or, sort of a new perspective that is kind of increasingly being embraced by, uh, different government and intergovernmental agencies that really understands this dynamic, exactly what I've been saying that, that, you know, human health is inseparable from the health of our environments from the health of other species and that we actually need to address these dynamics at the same time.

[00:35:45] And so this perspective is called one health. That's the, um, sometimes it's called planetary health and I think most often so far, it has been used to, uh, think about outbreaks and pandemics, these sorts of experiences like we've had with COVID, right, that are both dynamics that are profoundly Human impacted by human systems, but that also, you know, are related to ecological destruction and and cross species boundaries.

[00:36:17] And so I have some challenges with how one one health has been conceptualized so far, but I think that it is an important. Uh, change from how we, at least in a Western context, and again, as settler colonial context, have been seeing the separation of, of human health and the health of nature. And so I think that there's some potential there to really think about what it would mean to address some of these, uh, Issues, you know, not as separate, but thinking about them as connected.

[00:36:50] John: The creativity needed to express through words, the change that's needed is something that seems to be a common, a common thread through conversations, whether it's through policy or, or whatever. I think about the work that the Tusconians for the clean environment, you know, the fact that they came up with an acronym that expressed the primary pollutant At the Superfund site was such an active revolution to me.

[00:37:16] I'm like, Oh, it's such a great thing. I'm curious about your, just your perspective on the use of creativity as a tool with the work that you do, you know, because your work intersects with your art practice and all the different research that you do. Where do you see that need for it? No.

[00:37:33] Sunaura: It's interesting.

[00:37:34] This is kind of a hard question for me to answer because it's almost hard for me to pinpoint where we wouldn't need it. Um, you know, and also I think again, I would say if there were two kinds of central values in my home growing up, it would be creativity and curiosity. And so those ways of engaging with the world are so, so important to me.

[00:37:59] And I think partially right. It's about. envisioning ourselves outside of the options and boundaries and limitations that society puts on us, right? Disability activism is a really great example of this. Disability movements relied on some extremely creative, inventive ideas of what it meant to be a disabled person and what kinds of lives disabled people should be able to have for those kinds of creative visionings of imagining ourselves outside of the limitations that able bodiedness and ableism sort of put on us, that's an act of creativity.

[00:38:44] It's an act of creativity. It's an act of imagination. Um, and I think that could be said for, you know, all of these, these social movements that first have to be able to imagine themselves outside of, of those boundaries of whatever has been projected onto us, you know. And I think on an ecological context, that's really important to, I think creativity and is, is also so important in, in terms of its relationship to, to in my opinion to empathy, right?

[00:39:16] That there's something about being able to imagine oneself experiencing what another is experiencing, that it is also an act of creativity. And that is so important, again, for, you know, thinking about our own sort of human dynamics with each other are, you know, social dynamics categories that are placed upon us and stuff, but also again, thinking about the broader more than human world that these animals that we also exist with our animal, our animal neighbors, what is it that they are experiencing when we destroy their habitats when they are running from wildfires?

[00:39:55] So I think maybe that's partially it for me is that creativity is, is central to being able to imagine the world in a different way, which need right now.

[00:40:06] John: As we're wrapping things up, I would love to take a moment to, if it's close our eyes or whatever, just to, to your point, envision that world, what is that world to you?

[00:40:14] What does it look like? What does it feel like? What does it sound like? What does it taste like?

[00:40:21] Sunaura: Yeah. I wish I knew, you know, I mean, I think it's a world where human beings and non human animals and ecosystems are not valued for their productivity are worth in some sort of way. Um, economic sense. Where there's that space and time for people to have that creativity and where they can experience each other living on this amazing, mind blowing planet with all these mind blowing other creatures on it. I think it is a world that is also, from a disability perspective, not a perfectly healthy, pristine, cured world, right? I don't have and I don't want a eugenicist vision of, of our future of what I want. I think there's profound value in just the reality of change and atrophy and aging and disablement and illness, that these are experiences that are integral. You know, we should do everything we can, of course, to resist and stop the perpetuation of mass. disablement and injury by exploitative and violent systems.

[00:41:43] Right. But that there's also the reality that injury and that kind of vulnerability are part of our world. And I find them very valuable, actually, which I think is also one of the kind of strange paradoxes of the book. Is that, you know, people might see the cover or read the title or, you know, and just have this sense of like, oh, this is going to be a foreboding book.

[00:42:09] And on one level, it is. But on another level, to me , living with multi species disablement doesn't have to be foreboding. It can also, if responded to in an anti ableist way, anti capitalist sort of way, I think there can be hope in that. And I think that's part of what I'm trying to get across in the book.

[00:42:30] Yeah. So lots of thoughts, you know, I'd be curious what that world would look like to you.

[00:42:35] John: One of the things that I feel like I gained most from your book was that there was the strength in vulnerability to your point, that there's this conversation around that idea, but it was something I just found really, really hopeful for me. And then to answer your question, in my research, I found that as of June 6th of this year, there are 1, 340 Superfund sites that are listed on the national priorities list in the U. S. And I think that for me to start off with, it would be to have a conversation where we don't end up with more sites like that, whether it's a Superfund site or some other thing that we haven't thought up yet, that's going to turn into a catastrophe at the scale of a Superfund site. But it would be a place where we have the space to what you're saying, to have more creativity in the world and less superfund sites.

[00:43:24] Sunaura: I love that. So yeah. Yeah. And it would definitely, it would have to be a very different world for there to not be superfund sites. So yeah.

[00:43:33] John: I have this vision of the world, hundreds of years from now where that exists. And I believe so wholeheartedly in it that I can I can draw it. I can picture it. And to me, it's real.

[00:43:46] Sunaura: That's that's what it is about, right? That's I think this envisioning and that creativity and imagining that I do. I feel like that. Is so incredibly important and we need to hold on to those visions.

[00:43:59] John: Yeah. So what is next?

[00:44:01] If you, if you're able to share, I'm curious, cause I have to go back and now read, Beasts of Burden as well, because I enjoyed this book so much. And so I'm curious what's coming up next.

[00:44:12] Sunaura: Oh, thank you. Um, well, to my point about, just slowness and time, I think right now I'm, really just enjoying celebrating having disabled ecologies out in the world, seeing where it lands, seeing where people take it, how it's taken up in various conversations.

[00:44:31] This book took me eight years, so I'm just really trying to enjoy having it out right now. I am a project oriented person. I feel uncomfortable if I don't have projects. So that said, there are big bits and pieces brewing in the mind. Um, but, uh, but I'm actually, I'm, I'm kind of trying to force myself to just be like, just, just take it slow, just enjoy this.

[00:44:56] So that's, that's what I'm doing right now. I'm having a great time doing podcasts and talking about the book at various events and stuff, so it's been great.

[00:45:04] John: Well, Sunaura, rest is radical, so I think you're on to something with taking some time off and making space for that, but I just wanted to say thank you for joining me today, and it's been a real pleasure, not just this conversation, but getting to dive deep into your work and seeing the kind of human being that you are and the way that you walk through the world is a beautiful thing to me.

[00:45:27] And so thank you. Thank you so much. That means so much. And, um, your questions were so thoughtful and, I can't tell you how fun it is to also be able to have these conversations, you know, um, again, about this project that's taken me so long. So, and about ideas that are so important to me. So, so thank you so much for having me on the podcast and for your work.

[00:45:47] In this podcast as well.